Former great Oakland A’s catcher the late Ray Fosse looking upwards smile on face with catcher’s glove is one of the people the author will remember and be thankful for in covering A’s baseball over the years (file photo Athletic Nation)

My Farewell to the Green & Gold

By Mauricio Segura

As a lifelong fan of the Oakland A’s, who used to dream (like many) of donning a green and gold jersey, #21, playing centerfield, and hitting home runs into the ivy behind the bleachers (before Mt. Davis ruined that), writing these words feels like carving out a piece of my soul.

The ever-approaching finality of the A’s leaving Oakland is not just the loss of a team—it’s the tearing apart of decades of memories, a community, and the beating heart of baseball in the East Bay. For those who’ve been there since the beginning, watching games in the windy chill of the Coliseum, there’s an indescribable ache that settles in knowing this chapter is closing.

It feels like losing a loved one, something irreplaceable, where nothing will ever refill the void. It is with tears streaming down my face that I write these words—my farewell and tribute to an old friend.

The A’s have always been a team of movement—born in Philadelphia in 1901, where they first made history as one of the original American League franchises. Winning five world championships under the legendary Connie Mack, the A’s became a powerhouse of early Major League Baseball.

After a rocky tenure in Kansas City (1955-1967), they landed in Oakland in 1968. We welcomed them with open arms, and what a ride it’s been. The 1970s became the Golden Age of the A’s, with owner Charlie Finley turning the team into champions—and not just any champions, but a team that captured the imaginations of baseball fans everywhere.

Finley was a showman. He brought in oddities that left people shaking their heads and laughing, like the introduction of “The Mechanical Rabbit” that delivered new baseballs to umpires, or his insistence that the team wear white cleats—a move that was mocked at first but ended up setting a fashion trend that teams followed for decades.

It wasn’t just gimmicks that made those A’s teams legendary, though. On the field, they were a force of nature. Between 1972 and 1974, they won three consecutive World Series titles, with Hall of Famers like Catfish Hunter and Rollie Fingers delivering one clutch performance after another.

Who could forget the cannon arm of Reggie Jackson, “Mr. October” himself, or the speed of Bert Campaneris flying around the bases? These players didn’t just play the game; they electrified it, turning it into something bigger than a sport—a cultural moment.

Side note, did you know that Debbi Fields of Mrs. Fields Cookie’s fame was one of the original Oakland A’s ball girls? She was! And Stanely Kirk Burrel, who you know better as MC Hammer was a ballboy.

By the 1980s, the A’s reinvented themselves again under the fiery and relentless Billy Martin. The term “Billy Ball” became synonymous with aggressive, no-holds-barred baseball. Billy Martin was a manager with a spark, and he brought that spark to Oakland in full force.

Players like Rickey Henderson, who would go on to become the all-time stolen base leader, were at the forefront of this era. Henderson wasn’t just fast; he was a magician on the base paths, stealing more bases in a single season (130) than any other team in the league, then years later finishing his career as the king of steals with 1,406—a Major League Baseball record that may never be broken. Alongside him, players like Dwayne Murphy, Tony Phillips, and pitcher Steve McCatty embodied the hustle, grit, and toughness that came to define this period.

Then came the LaRussa years and the rise of the Bash Brothers—Mark McGwire and Jose Canseco. The late ’80s were a time of thunderous home runs, and the team was crowned champions again in 1989, winning the World Series in the aftermath of the Loma Prieta earthquake.

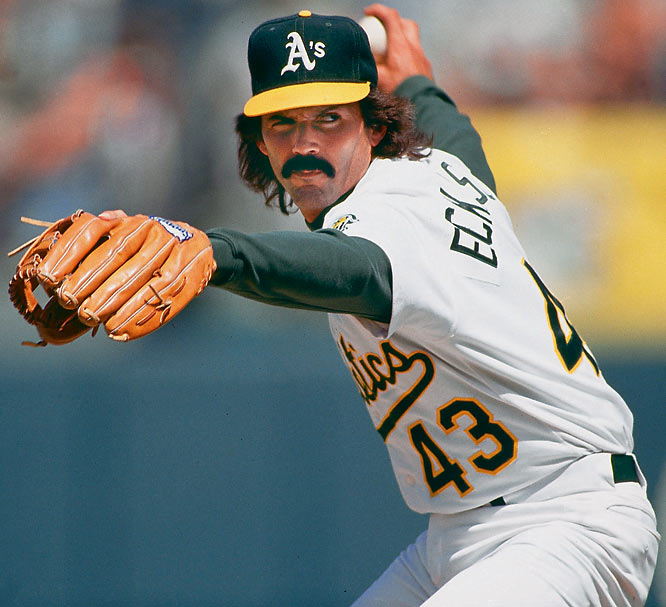

That series against our Bay Area rivals, the San Francisco Giants, became known as the “Earthquake Series,” a poignant and surreal moment in sports history that transcended baseball. The image of Dave Stewart staring down batters with a look of a tiger eyeing its prey or Dennis Eckersley pumping his fist after each pivotal strikeout is etched in our memories. And who can forget the heartwarming, gap-toothed smile of Dave “Hendu” Henderson? Every time he smiled, you knew something good was afoot.

In the 2000s, the A’s were ahead of their time with the Moneyball era. Billy Beane, the architect behind it all, revolutionized baseball with a strategy that turned conventional wisdom on its head. While teams like the Yankees spent hundreds of millions, the A’s thrived by analyzing data and exploiting inefficiencies. Players like Tim Hudson, Barry Zito, Eric Chavez, and Scott Hatteberg became household names, not for their superstar status, but for their incredible contributions to a team that embraced innovation and defied the odds.

And even now, with a team expected by everyone in the league to be thrown out with the morning trash, a special shoutout goes to players like Brent Rooker, Lawrence Butler, and Zack Gelof, who, despite the chaos swirling around them, continue to play their hearts out and win games for us. Their perseverance, despite resistance, has shown the utmost dedication and loyalty to their craft.

Through it all, something else stands out—the unwavering loyalty of the fans. The Oakland Coliseum, often called a “dump” by outsiders, was home for us. Sure, the plumbing was bad, and the seats were outdated, but it was our dump—where we witnessed moonshots and forearm bashes.

Our dump where, in May of 1991, Rickey Henderson proudly declared, “Today, I am the greatest of all time.” Our dump where Catfish Hunter and Dallas Braden achieved perfection on the mound almost 42 years apart. It will always be our dump, and we’re damn proud of it!

The stadium has reverberated with the chants of the fans who packed the bleachers, beating drums, blowing horns, and throwing themselves behind this team. Even as attendance waned in later years due to poor ownership decisions and the looming threat of relocation, Oakland fans refused to go quietly.

Who could forget the reverse boycott of 2023, when fans donned “Sell” shirts in protest of ownership—a movement so significant that one such shirt ended up in the Hall of Fame! That was more than a protest—it was a love letter to the team, a declaration that we wouldn’t go down without a fight.

Yet here we are, at the end of that fight. The A’s are leaving, and it’s hard to fathom a future without them in Oakland. But they leave behind a legacy, one that can never be erased. This city, with its rich and complicated history, has been the backdrop for some of the most incredible moments in the history of this beautiful game.

Even as the team moves to Sacramento, Las Vegas—or wherever the winds of ownership take them—those of us who lived and breathed Oakland baseball will carry these memories forever.

As the final out is recorded next Thursday afternoon, and the team leaves the Coliseum for the last time, our hearts will remain torn. But the memories we made—of championships, rivalries, legends, and wild innovations—will never die. We can only hope that somewhere, in the heart of Las Vegas or wherever the A’s land, they carry a piece of Oakland with them. Because no matter where they go, the spirit of the Oakland A’s will always belong to us.

In my ten years covering this final chapter of A’s baseball from the Coliseum press box, I want to give a thankful shoutout to three people who have made it so much more memorable: Amaury Pi-Gonzalez, the Spanish Voice of the Oakland A’s since 1977 and my mentor; Lee Leonard for countless hours of stories and laughs between innings… and during; and the late great Ray Fosse, who was always available for questions and advice. Thank you!

Mauricio Segura Golden Bay Times Die-hard Green and Gold since 1983