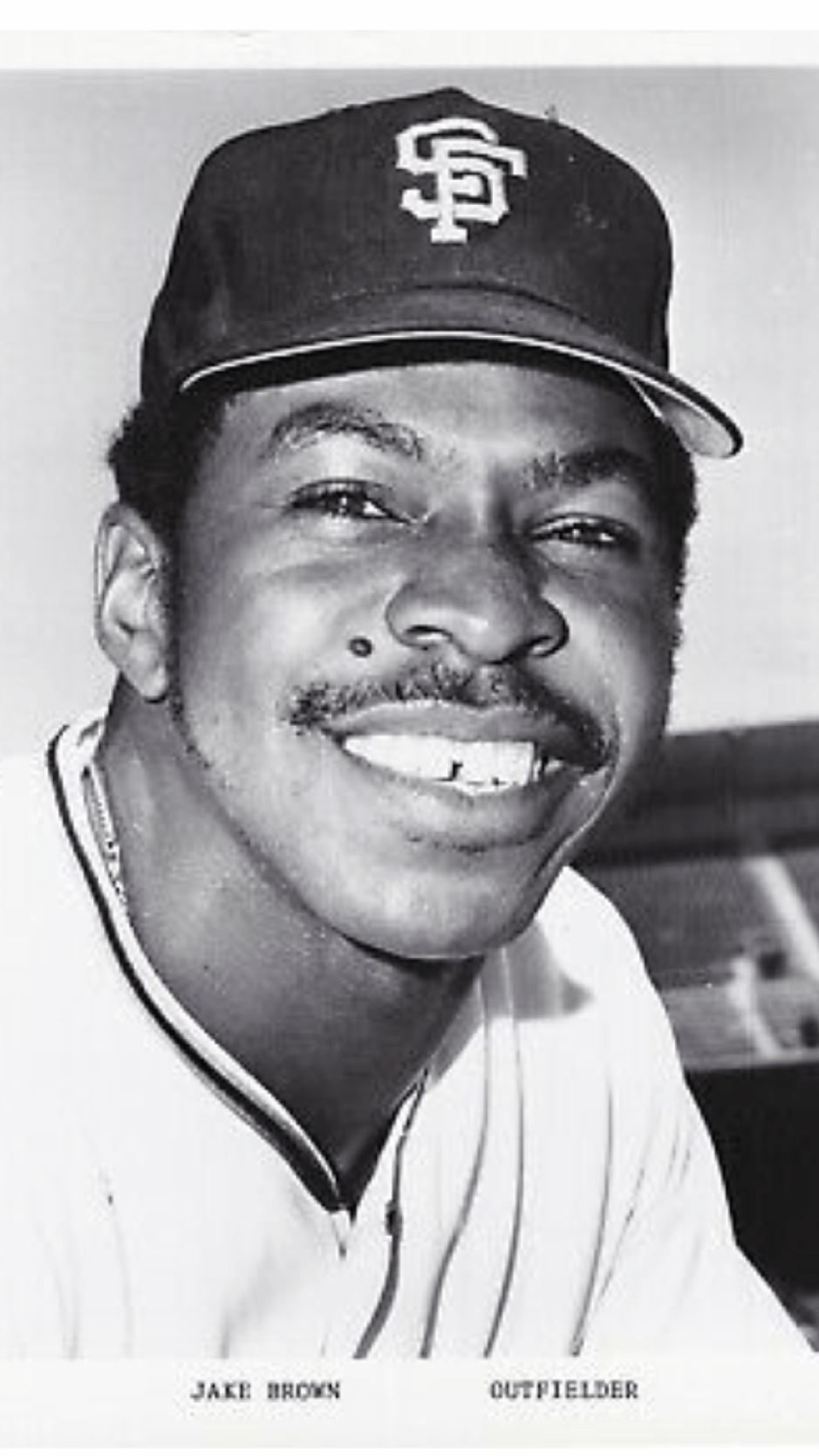

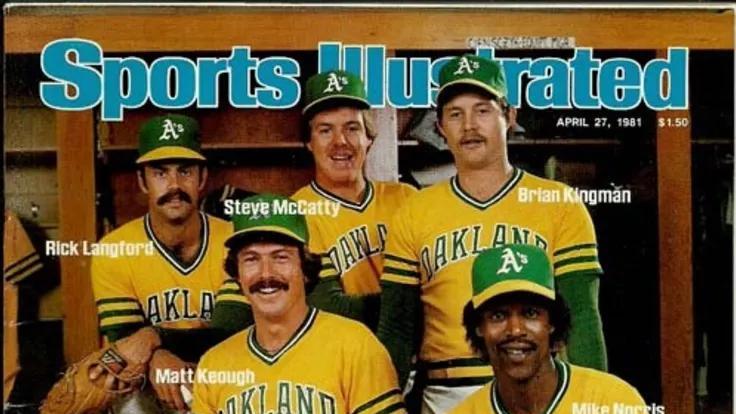

(photo from San Francisco Giants)

Jake Brown – OF – 1975 – # 32

He Was A Giant?

By Tony the Tiger Hayes

These days you typically don’t find top MLB prospects seeking off -season employment just to put food on the table.

You’re even less likely to find one who would jeopardize it all by working an industrial manufacturing job with the same inherent, hair-raising dangers graphically described in Upton Sinclair’s 1905 novel “The Jungle.”

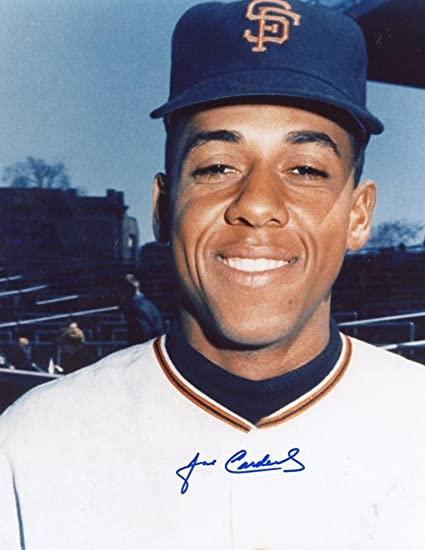

But that’s where former top Giants top draft pick Jake Brown – who appeared in 41 games for San Francisco in 1975 – found himself in October of 1973.

Unlike some athletes of that era who land cushy public relations jobs or sold Buicks and Oldsmobiles in the off season, Brown was elbows deep in the nitty-gritty.

After batting .290 with 80 RBI for Triple-AAA Phoenix that year, Brown traded in his flip-down sunglasses and polyester baseball threads for protective goggles and fire retardant coveralls to work behind limb endangering heavy machinery at a Texas steel factory.

Predictably, the results were, well, predictable.

In an instant Brown went from being a contender for a major league roster spot to becoming a candidate for amputation.

Why Was He a Giant?

Originally a 33rd round draft pick by Minnesota out of high school in Houston, Brown instead opted to attend Southern University and A&M College in Baton Rouge. There, he would significantly improved historical draft status with two standout seasons for the Jaguars.

Brown was subsequently selected with the Giants’ first round pick (second overall) in the secondary phase of the June, 1969 amateur draft. The now defunct secondary phase was held for players who had previously been drafted.

The muscular OF was faced with a lot of competition in the Giants minor league rungs, but was steadily progressing when the unheard of happened.

Before & After

The prospective big leaguer was working on a sheet metal assembly line when his left arm was caught between a lathe and a piece of sheet metal – the appendage was viciously and severely lacerated, and also fractured in two places.

Amputation was strongly considered.

“I figured that was it. I just knew I was going to lose my left arm,” Brown said two years later.

But skilled Texas neurosurgeon Dr. Richard Eppright discovered a single nerve still intact running the length of his arm.

Miraculously, Jake was able to wiggle his pinkie finger and the arm was saved.

Brown lost a lot of blood and spent two weeks intensive care. The arm was saved, but what about his baseball career?

Despite his harrowing encounter, Brown was determined to play in the major leagues.

He would miss all of 1974, but by 1975 Brown was ready to go.

Brown began the season at Double-AA Lafayette and at age 27 proved he had his stroke back – batting .307 in 19 games for the Drillers.

He soon got the call he was long waiting for from the mezzanine level offices of Candlestick Park.

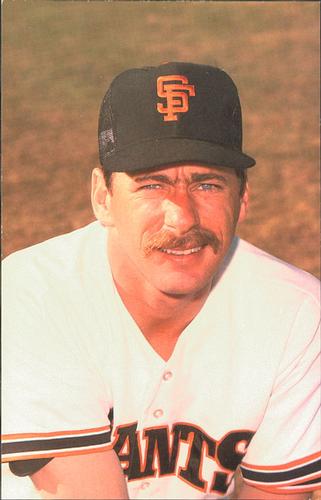

Skipper Wes Westrum was on the horn welcoming him to the Major Leagues.

Brown made his MLB at Candlestick Park in a Saturday afternoon blow out loss to the Cardinals, entering the game in the late innings as a defensive replacement.

Afterwards an emotional Brown expressed his gratitude to the Giants organization.

“ A lot of clubs would see a guy get hurt that bad and forget about them. I have to thank them for this opportunity,” Brown said.

Brown encountered his share of problems with the Orange & Black, but would play out the ‘75 season as a backup OF and pinch hitter for SF – hitting .209 in 43 at-bats.

Brown found himself back at back at Lafayette in 1976. In mid-season, he was dealt to Atlanta along with three other players including 1B Willie Montanez in exchange for IFs Darrell Evans and Marty Perez.

Brown would retire from baseball following the ‘76 season having not returned to the majors.

He Never Had a Bobblehead Day. But…

It appeared Brown was beginning to feel his big league sea legs when he belted the ball hard three times, including a booming double in a 8-6 loss at Philadelphia (5/28/75). In his next start, Jake batted in the cleanup spot and whacked a three-run, bases-loaded double off Dave McNally in the first inning of a 13-5 win at Montreal (6/1/75).

But in keeping with the snake-bit theme of his career, the next day’s papers had nary a mention of Brown’s three-RBI two-bagger.

Instead, splashed across the front page of the San Francisco sports sections was a generous photo of the Giant knocked out cold on the the Jarry Park warning track.

Brown had had a bead on a long Larry Parrish, 3rd inning blast. Jake got leather on the drive as he soared towards the outfield fence. Initially, it appeared the popular rookie had made a phenomenal catch.

But after flying though the air, Brown’s face bashed into an outfield support post. The ball bounded off his glove and skipped over the wall for a home run.

Brown suffered a fractured cheek bone and a concussion and would be out of action for two weeks.

Giant Footprint

Sadly, in 1981 Brown would pass in Houston from Leukemia.

Though he died way too young – just 33 – let’s hope that his final days Brown took solice that he he was able to accomplish to big league dream.

“It was a miracle my arm was restored,” Brown once said. “When I knew they’d somehow fixed it, I was determined to perform for the Giants.”

That, he did.