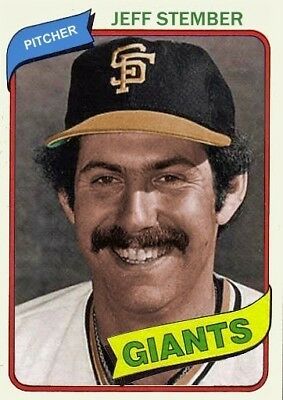

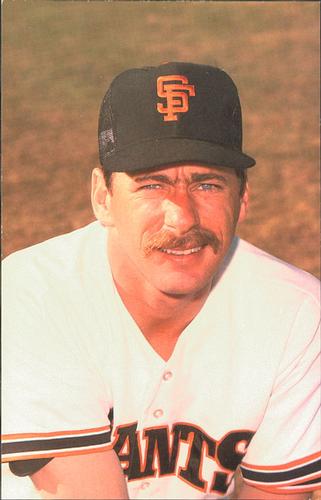

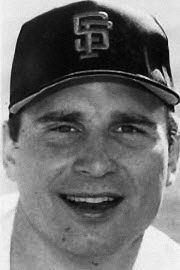

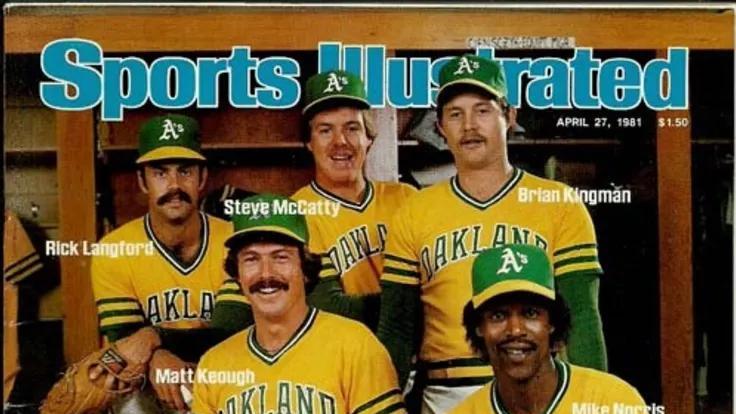

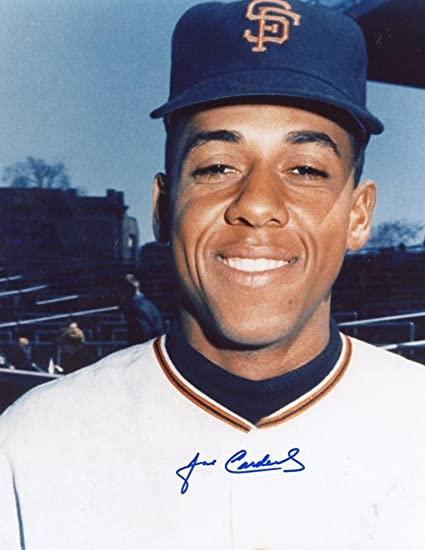

Former San Francisco Giant third string catcher Brad Gulden and the answer to the Giants trivia question where did former Giant manager Roger Craig come up with Humm Baby ( circa 1986 courtesy of Mothers Cookies)

He Was A Giant? … Brad Gulden

35 Years Ago Humm-Baby Was Born

By Tony “The Tiger” Hayes

Brad Gulden – C – 1986 – # 10

He was a Giant?

Brad Gulden’s baseball reference page shows he batted a paltry .091 in 17 games for the 1986 Orange & Black.

What it doesn’t show is the largely forgotten role the third -string catcher played in forging the rebirth of a long-dormant winning culture in San Francisco and his uncredited contribution to one of the best marketing campaigns in club history.

From 1983-85 Bay Area baseball fans labored through three consecutive seasons of moribund Giants baseball. The Candlestick nine bottomed out in 1985 when the club lost a west coast worst 100 games.

Late in the ‘85 season Giants owner Bob Lurie took a bold step and cleared the decks. Out were long-time company men Tom Haller and Jim Davenport as general manager and field manager respectively and in was outsider Al Rosen in a newly created role of club president. Rosen’s first move was to hire former big league pitcher Roger Craig as manager.

Personality-wise, the urbane, buttoned-down Rosen and the homespun, horse riding Craig we’re complete opposites. But each man held the same laser focused opinions on how the team should be run.

They could not guarantee victories, but a few things were certain.

The team would play fundamentally sound baseball. The Orange & Black would hustle. And possibly most importantly, under no circumstances would anyone associated with the Giants ever bitch about, rip or denigrate Candlestick Park – no matter how complaint worthy the miserable dump was.

In 1986, new faces (and a few familiar ones) dotted the Giants spring training fields. The list included the heralded first round draft pick 1B Will Clark and the greatest Giant of them all, Willie Mays, who was officially brought back to San Francisco for the first time since 1972 in an advisory and camp instructor role.

Among the throng of new players was Gulden, a journeyman back-up catcher who came to camp on a minor league pact.

Talent wise, the burly backstop did not grade out well. He was a lifetime .220 hitter, a slow runner, and his throwing arm was about what you would expect from a well traveled 30-year -old receiver.

But what Gulden lacked in All-Star physical talent he compensated with intangibles. He blocked the plate like a 49er, Gulden communicated well with pitchers and he constantly hustled and never groused.

He wasn’t flashy, but Gulden was as reliable as the old pickup truck Craig drove around his California ranch in the off season. And after one particularly inspiring spring training afternoon of breathlessly chugging after foul pops and two-timing it to first on routine grounders – Craig declared for the first time what would become his trademark buzzword to describe a Giants player.

“He’s a “Humm-Baby,” said Craig when quizzed about Gulden. “He’s the kind of kid who will bust it for 10 innings and give you 150 percent.”

Craig explained that “Humm-Baby” was an old sandlot expression – a combination of “Hum it in there” and “Come on Baby.”

“Humm-Baby means aggressive, hard-nosed baseball,” Craig related. “It can mean a great double play, a well executed hit-and-run or a beautiful girl.”

O.K.

Though nobody could ever recall hearing the phrase before, the motto quickly became de rigueur for Giants fans.

Why Was He A Giant?

The Giants opened 1986 spring training with just one hold over at the catcher position – starter Bob Brenly.

Rookie backup Matt Nokes was dealt in a trade to Detroit that returned another unproven young catcher, Cal product Bob Melvin, and RHP swingman Juan Berenguer.

Next veteran receiver Alex Treviño, was swapped to the Dodgers for future starting OF Candy Maldonado. That trade was notable not only for its lopsided result in the Giants favor – but also because it noted the first trade between the two rivals in some two decades.

Another 20 years would pass before the adversaries completed another deal.

A minor league free agent, Gulden was added to the 1986 spring roster for catching depth after spending all of 1985 with the Triple-AAA affiliates of the Reds and Astros.

Gulden was far from a lock to make the Giants major league opening day roster in 1986. His chances were reduced even more due to a cut back in roster spots that season from 25 to 24 players.

But the Giants choose to open the year with three catchers – including the hard scrabble Gulden.

“He shook hands with me about six times and even kissed Al!” said Craig after telling the beefy backstop the good news. “Gulden worked hard. He exemplifies the type of player we want.”

Before & After

Gulden entered pro ball as the Dodgers’ 17th round draft selection in 1975. He signed immediately and reported to Class-A Bellingham at age 18.

After hitting an unstoppable.398 as a senior at Minnesota’s Chaska High School that spring, Gulden’s average plummeted to .163 during his first summer of minor league ball.

But Gulden kept at it, climbing steadily through the Dodgers farm system.

In 1978, Gulden catapulted Triple-AAA Albuquerque into the Pacific Coast League championship series after his 10th inning, game winning hit completed a three-game sweep of Salt Lake City in the Eastern Division playoff series.

Not surprisingly the rugged receiver pounded the two-RBI knock while nursing a broken finger. He was rewarded with a call-up to Los Angeles and finished the ‘78 season with the parent club.

Tragedy led to Gulden receiving his first extended big league look in 1979. Traded to Yankees during spring training, Gulden was unexpectedly thrust into New York’s lineup in mid-season after the shocking death of Thurman Munson. In a 40 game trial for New York, Gulden batted just .163.

Gulden logged time with the Mariners and Expos after that, but it would take another four seasons before Gulden received his next extended look-see. In 1984, Gulden appeared in a career high 107 contests for Cincinnati, batting .226, 4, 33.

He Never Had a Bobblehead Day. But…

Gulden’s signature on-field moment as a Giant came during a chaotic 4-hour, 18-minute, 12-inning affair at Los Angeles in the fourth game of the ‘86 regular season.

Five batters were hit by pitches, there were three wild pitches and five errors (four by the Dodgers). And just for fun, two Giants catchers (Brenly and Melvin) filled in at third base.

Fueled by a three-run Jeffery Leonard long ball, San Francisco took a commanding 8-1 advantage into the bottom of the 7th. Then the Dodgers bats came alive, scoring four runs in the 7th and adding three more in the 9th to tie the game.

Gulden, who entered the game in the 9th as a defensive replacement, had a prime opportunity to drive home the go-ahead run in the 10th.

With Maldonado on second with one out, Los Angeles ace reliever Tom Niedenfuer intentionally walked Clark to face Gulden. The move paid off for Tommy Lasorda’s minions as the intimidating Niedenfuer blitzed Gulden with three straight blazing fastballs.

The score was still knotted at 8-8, when almost the exact same scenario repeated itself in the 12th.

With one out, Maldonado ripped a double to left. Dan Gladden followed with a line drive single to center, but ex-Giant Enos Cabell – who remarkably was playing center field for the first and last time in his 15-year career – hurled a perfect peg to Dodgers catcher Mike Scioscia to nail Maldonado for the second out. Gladden took second base on the throw.

With first base open, Niedenfuer again walked Clark purposely to bring up Gulden again.

This time Gulden turned the tables on the intimidating Dodger, whacking a pitch into center field to drive in Gladden. An aggressive Clark would be thrown out at third on the play, but the Giants took an 9-8 lead to the bottom of the 12th.

Jeff Robinson peacefully set the Dodgers down in order in bottom of the 12th to secure the victory.

After failing his team in the 10th, Gulden vowed not to allow a de je vu situation in the 12th.

“The first time up (Craig) told me, ‘You’re going to win the game.’ And I struck out,” Gulden said afterwards. “The second time, I said ‘Brad, relax, relax.”

But even if Gulden had whiffed again in that spot, there was little chance of seeing a white flag raised in the Orange & Black’s dugout.

“We were fired up,” said Gulden. “We could have played all night.”

Giant Footprint

After the euphoric victory sparked by Gulden , San Francisco went on to win seven of their next 10 games. The upstart Giants would finish April with a 13-8 record – posting their first month of winning baseball since September of 1983.

The Giants unforeseen success would continue. At the ‘86 All-Star Game break, the club shockingly sat atop the NL West with a 48-40 record.

Gulden’s season however peaked with his game winning hit off Niedenfuer. After going hitless in his next 18 at-bats, Gulden was optioned to Triple-AAA Phoenix in favor of OF/1B Mike Aldrete. The catcher remained in the desert until September when he was recalled to the parent club to finish out the season.

There was little fanfare when the Giants released Gulden two weeks after the conclusion of the ‘86 season in which the club finished third, recording their first winning record since 1982 (83-79).

The Giants were officially done with Gulden at that point. But the “Humm-Baby” rally was just getting warmed up.

At a flashy news conference prior to the start of 1987 season, the Giants introduced their promotional campaign for the highly anticipated upcoming season. The catchphrase for the television, radio and print advertising was… “Humm-Baby, It’s Gonna Be Fun.”

The Giants were no strangers to creative ad campaigns – hello, “Croix De Candlestick” and “Crazy Crab” – but this campaign was different because it was supporting what was expected to be a winning team – not a tongue-in-cheek gag for a club with no legitimate shot.

The “Humm-Baby” catch-phrase would be ubiquitous during a Giants remarkable 1987 season that saw the club make it to the playoffs for the first time since 1971.

The “Humm-Baby” phrase appeared everywhere from t-shirts and freeway billboards to bumper stickers. Craig’s credo was even stenciled on to Orange & Black boxer shorts pedaled at Candlestick souvenir stands.

For the first time in years it was cool for Johnny and Jenny Public to rock Giants gear.

The Giants would ride the wave of good times throughout the ‘87 season without nary a mention of Gulden – the very player who inspired the “Humm-Baby” lifestyle.

When the Giants popped corks on their 1987 NL West crown that September, not only was Gulden not present – he was absent from pro ball for good – having gone home to Minnesota to start a new career as a firefighter.