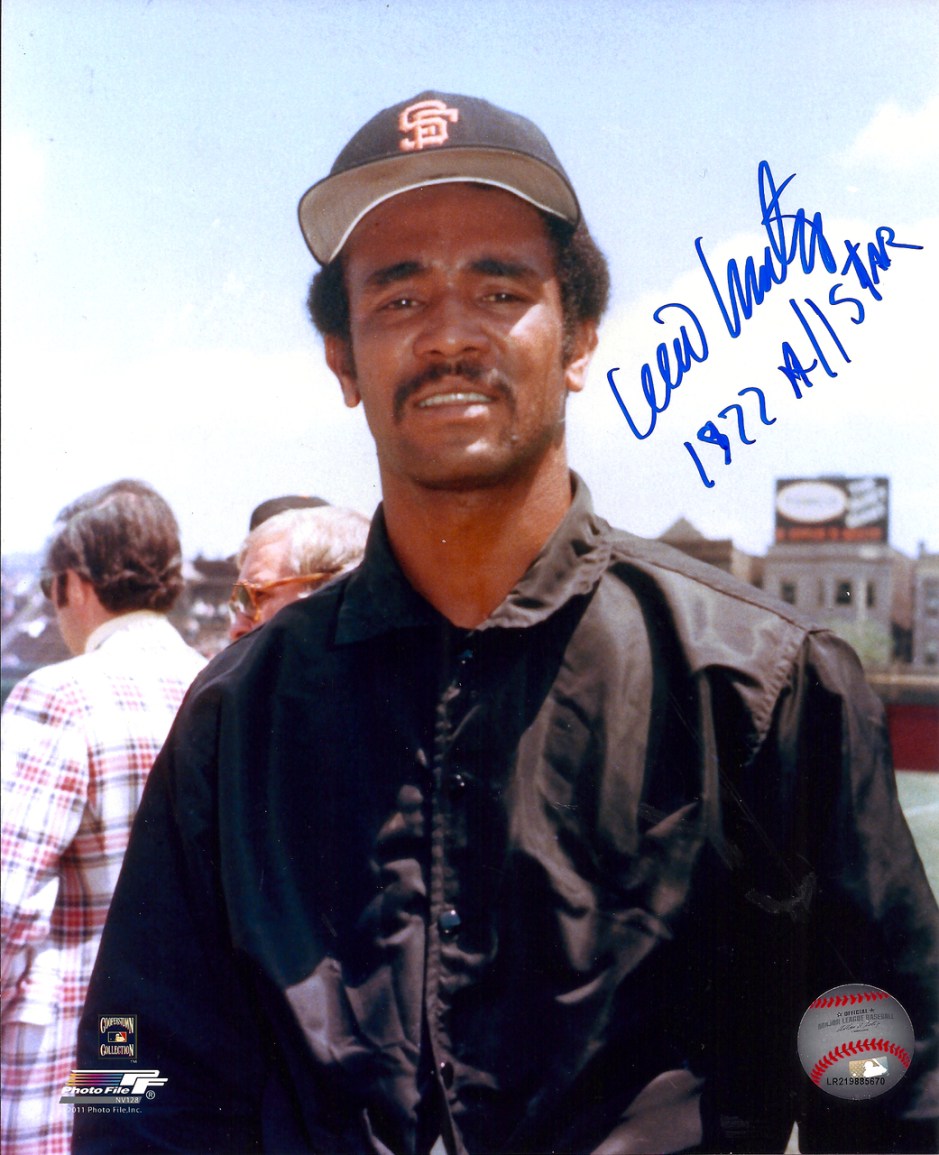

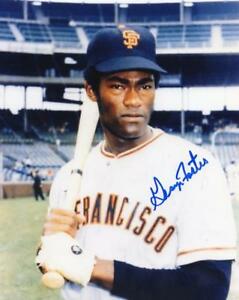

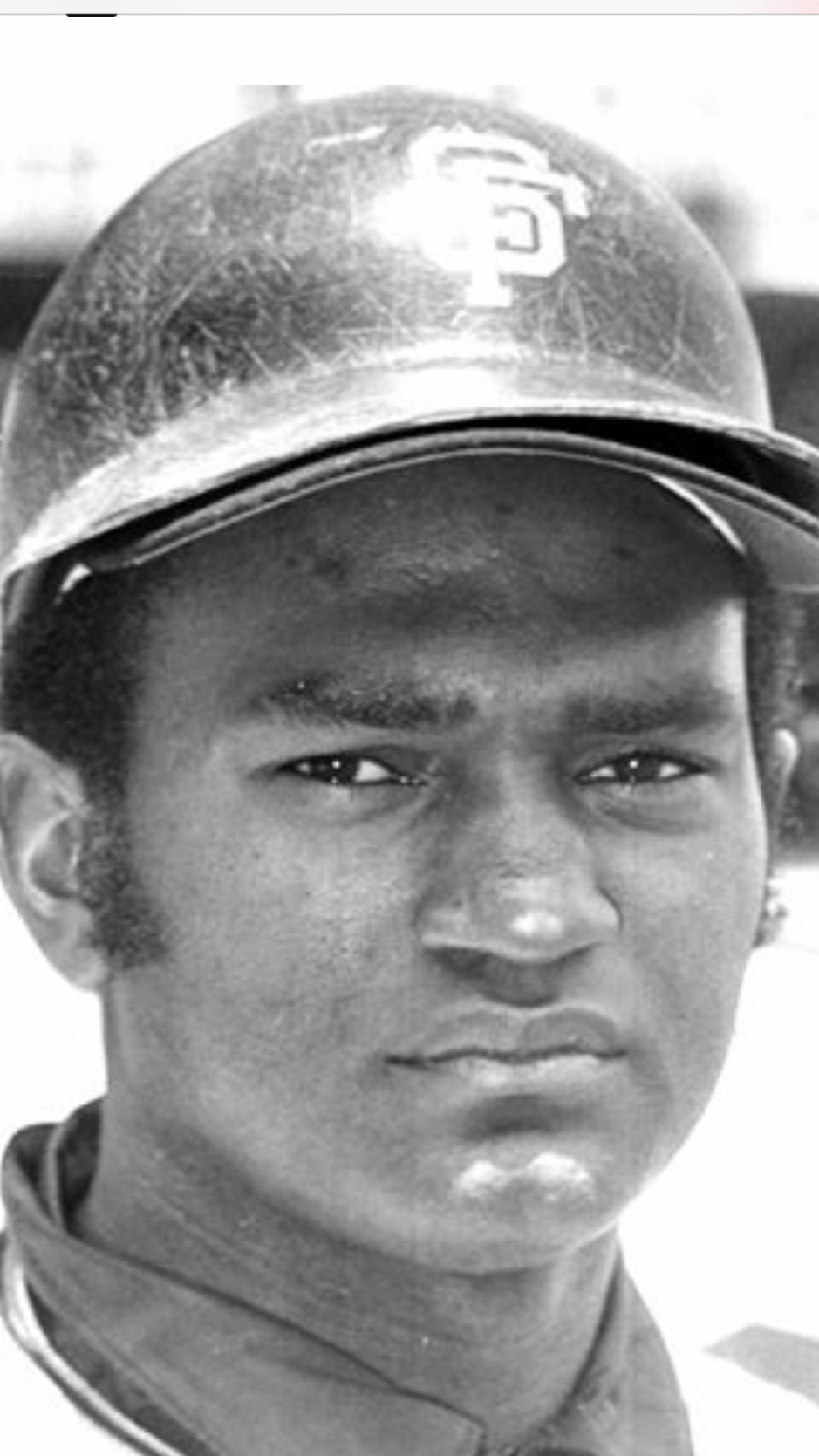

Former San Francisco Giants George Foster circa 1971 around the time of his rookie season played for the Giants until May 1971 before being traded to the Cincinnati Reds (ebay file photo)

George Foster -OF – 1971- # 14

He Was a Giant?

By Tony “The Tiger” Hayes

The San Francisco Giants never considered George Foster to be anything more than an understudy to his athletic idol – Willie Mays.

So it was ironic that six years after the Orange & Black dealt Foster to the Cincinnati Reds in late May of 1971, in exchange for a package that turned out to be an empty box, that the late blooming All-Star became the first hitter to punch 50 home runs in a big league season since… you know who.

Foster would finish his border line Hall of Fame career with 347 home runs and 1,235 RBI. He was 1977 National League Most Valuable Player; started six All-Star Games (MVP in 1976 Mid-Summer Classic); and was a member of two World Series Championship teams.

The trade of Foster has come to be known as one of the most embarrassingly lopsided deals in west coast Giants history – and rightfully so – but in the late spring of 1971, the ill-fated swap hardly caused a ripple throughout the Major Leagues.

Foster’s major league sample size was so inconsequential and the naturally shy backup’s demeanor so deferential, that Foster was a virtual unknown 100 yards beyond Candlestick Park’s boundaries.

Cincinnati skipper Sparky Anderson wasn’t even sure what he was getting back in Foster.

“I haven’t seen much of him,” Anderson admitted to the Cincinnati Enquirer. “The only way to find out about him is to stick him out there and see what he does.”

But those who knew the introverted Foster best – his teammates – took the unusual step of ripping the transaction the day it went down.

They recognized the trade as a stinker from jump street.

“I can’t understand this,” said Giants breakout outfield talent Bobby Bonds. “George is a very promising player and I don’t know why he was traded.”

The typically soft-spoken Giants superstar first baseman Willie McCovey added: “There is no telling what can happen in baseball. It is awfully hard to figure out.”

At the time of the trade – in which the Giants received rookie shortstop Frank Duffy and journeyman right-handed reliever Vern Geishert – the club was without starting left fielder Ken Henderson who was sidelined with a groin strain – making the deal all that more curious.

“Who’s going to play the outfield?” an anonymous Giant asked the San Francisco Examiner’s Bucky Walter. “The trade deadline is June 15, couldn’t they wait until Henderson is ready to play?”

“We need outfielders not another shortstop,” complained another unnamed Giant.

The diffident Foster also stated his angst, voicing a public opinion for the first time in his career about… well, anything.

George was especially unnerved that it was Lon Simmons, of all people, who informed him of the trade. Now, Foster had no quarrel with the Giants’ baritone play-by-play man. The thing was, the 22-year-old just didn’t expect to receive orders to clear out his locker stall from someone who had just concluded a read for Lowenbrau beer.

“I learned of the trade via the radio… during the 6th inning without any notification from the front office,” a choked-up Foster told local scribes after the Giants crumpled the visiting Expos 8-3 on a bright Saturday afternoon (5/29/71).

Sans Foster, the Giants would go on to play winning ball the rest of the 1971 season, trading daily punches with the Dodgers before winning the National League flag by one game in the legendary Mays’ final full season in Giants mufti.

There would be no more hand-wringing in Giants-land regarding Foster’s departure the rest of the ‘71 season – nor frankly for the next few seasons.

It would take until 1975 before Foster fully matured as a power hitter and began wrecking havoc on opposing pitchers in a fashion that brought to mind the one and only “Say Hey, Kid.”

Why Was He A Giant?

After two short stints with the big club in 1969-70, Foster broke camp with the Giants in 1971. At the time of the trade to Cincinnati, Foster was doing about as well as expected, batting .267, 3, 8 in 36 contests as Mays’ caddy on a surging Giants club that led the National League West by nearly 10 games.

In his most memorable game with San Francisco, Foster batted 4-for-4, with a double and solo home run and three RBIs in a 5-3 road clocking of the Braves (4/28/71).

The ‘71 club featured a mixture of established Giants stars (Mays, McCovey and storied right-handed starting pitchers Juan Marichal and Gaylord Perry), plus a new breed of San Francisco charges – including the speedy, power-hitting Bonds, flashy second second baseman Tito Fuentes and a fresh-faced left side of the infield comprised of a pair of Bay-born rookies: third baseman “Dirty” Al Gallagher – the first native San Franciscan to play for the west coast Giants – and baby-faced shortstop Chris Speier of Alameda.

So why upset the apple cart and trade Foster in exchange for Duffy, an untested rookie, and ham and egger Geishert.

The answer may have arisen from the pitching side of the Giants clubhouse society. Decades after his final MLB game, Foster spoke of an old school Giants clubhouse where battle scarred athletes ruled the roost.

“The veteran players did not speak to the rookies. For awhile, a couple of guys didn’t speak to me, unfortunately, they were pitchers,” Foster recalled in an interview with “The Road to the Show” (YouTube) “So if you made a mistake in the outfield, they wanted to get you out of the lineup. They’d tell the manager ‘don’t play that kid when I’m pitching.’”

Gaylord Perry was a Giants pitcher who was notoriously hard on young teammates who bungled plays behind him. The taciturn Perry was known to display his pique with dismissive body language or by directly chewing out shoddy defenders right on the spot.

In one Perry start in ‘71, Foster butchered a couple of batted balls which lead directly to 4-1 Giants loss at Houston (5/21/71).

It’s quite possible that Perry privately grumbled to Giants manager Charlie Fox – a former catcher with pitching and defense-first mentality – about Foster’s defensive shortcomings.

Now, we’re not saying Gaylord forced the trade of Foster to Cincinnati, but the fact is, soon after his kick-the-can performance at the Astrodome, George was sent packing.

For San Francisco fans sake, let’s just hope the Giants didn’t foolhardily leave 344 potential home runs on the table and deal a future All-Star just because of a random bad day in the field that left Perry with a knot in his jock strap.

Before & After

Born in Alabama, Foster’s family joined the great southern migration to bustling northern and western U.S. cities in the mid-1950s, settling in the Los Angeles region. Though a young George grew up in the heart of Dodgers country, he was a devoted Willie Mays acolyte and simulated the celebrated Giant’s every move.

So imagine Foster’s delight when the Orange & Black scouted and signed him out of Torrance’s El Camino junior college. Within two years, Foster was lockering about 20 feet from Mays.

While some of the more experienced Giants kept rookies at an arm’s length, that was never the case with the warm-hearted Willie.

Just as he had taken fledging Giants from a previous era under his wing (McCovey, Willie Kirkland, Leon Wagner) Mays did the same with the following generations of young Giants.

In the case of Foster, Mays made sure he had plenty to eat.

“Bobby Bonds and I were were roommates and during spring training we would always go by Willie’s room at dinner time and pretend we we’re testing his food – like poison control- taste it make sure everything was fine,” Foster said with a wink in that same YouTube video. “We saved meal money by going to eat his steaks. We’d say ‘everything’s fine.’ And Willie would order more food for himself.”

Foster also discovered after his trade to Cincinnati, that Mays had called ahead to the Reds’ Pete Rose with a request from one All-Star to another.

“He told Pete, ‘take care of this kid,” Foster revealed years later. “It was heartwarming that Willie was still watching over me by making sure people were taking care of me.”

Foster actually walked into a pretty good situation with the Reds. With Bobby Tolan lost for the season with a Achilles injury, George took over in center field immediately in ‘71. Though he received plenty of big league experience that season, the trial run proved Foster still had lots of work to do on his journey to becoming an all-time great.

Over the next three seasons, Foster rotated between the Reds lineup, the bench and even Triple-A for extended stretches.

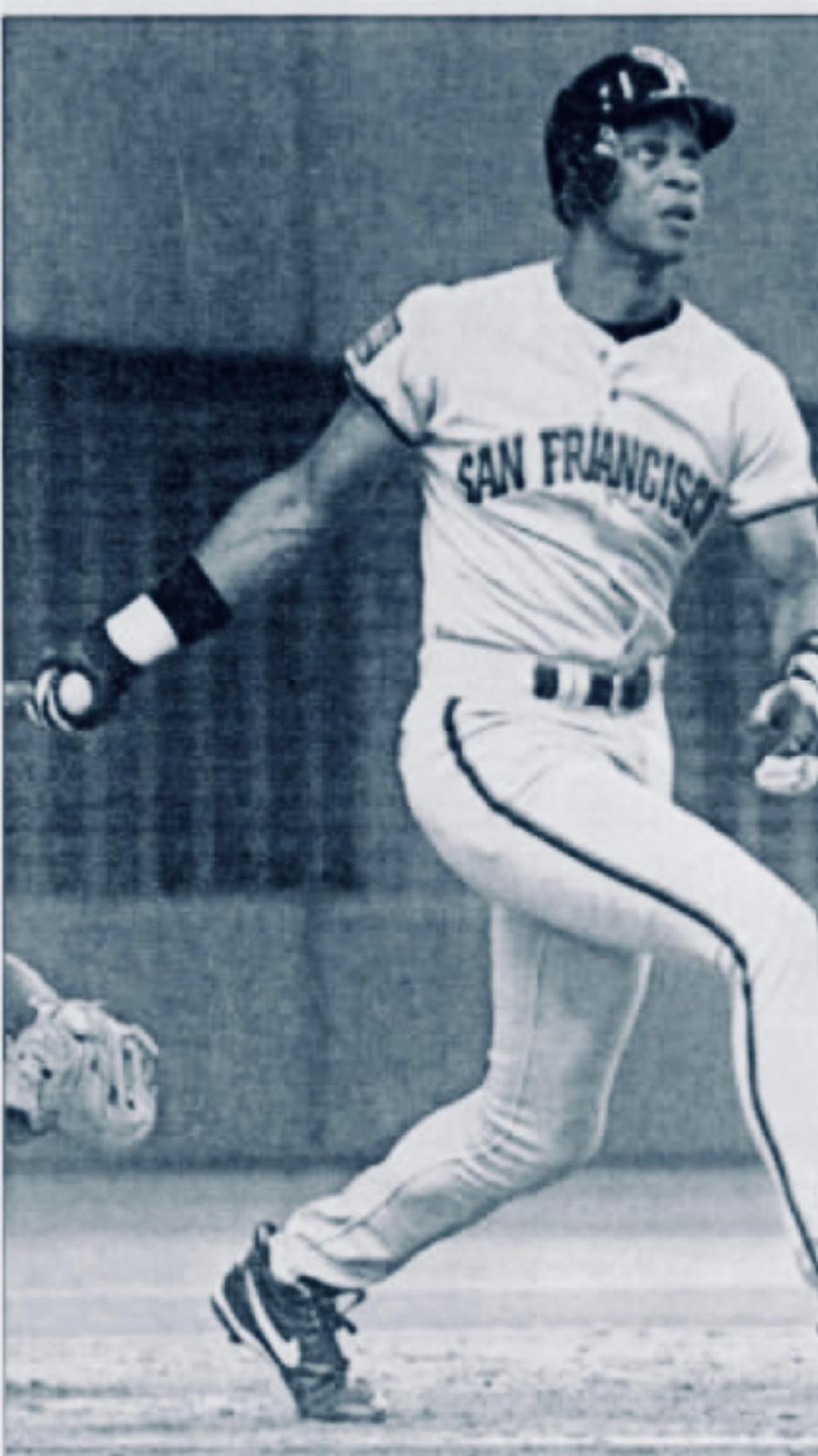

It wasn’t until ‘75, when Rose shifted from the outfield to third base, that Foster became a permanent member of the Big Red Machine’s celebrated every day lineup.

Cincinnati won back-to-back World Series titles in 1975-76 featuring a roll call of superstar hitters, including: Rose, Joe Morgan, Tony Perez and Johnny Bench – but Foster was the Reds’ cleanup hitter.

Foster would not only lead the heavy-hitting Reds in RBI – but topped the entire NL in the key stat for three straight seasons from 1976-78.

In 1976, Foster was in contention for the Triple Crown for a good portion of the season – finishing at an sterling .306, 29, 121.

At age 30, the introverted slugger was also slowly breaking out of his shell.

After the ‘76 campaign, Foster raised eyebrows when he self-appointed himself league Most Valuable Player. Sheepishly, Foster was compelled to walk back those comments when he realized his teammate Joe Morgan was voted the honor.

Foster brushed off the fopaux and returned with an even better campaign in 1977. He upped his average to .320 and again was numero uno in the RBI column (149). This time around Foster went extra bananas with the home runs – bopping 52 long balls. No batter had reached the half century mark in taters since Mays also walloped 52 in his 1965 MVP campaign.

In ‘77, Foster was the clear and obvious pick for MVP.

Foster further solidified his superstar status in 1978, leading the NL in HR (40) and RBI (121). His numbers tailed off slightly in 1979-81, but he was still among the best power hitters in baseball.

In 1982, the Reds went in a different direction and traded Foster to the lowly Mets for pitching. After a decade in homespun Cincinnati, the relocation to cynical New York proved to be a difficult move for the sensitive Foster.

With the fabled Reds, Foster was part of a star-studded ensemble cast in a cash-box certified extravaganza. With the bungling Mets – Foster’s name was the only one atop the marquee of a panned revival in a rundown off-Broadway theatre with threadbare seats. In 1982-83, Foster labored though his first losing seasons since 1971.

By 1986, the reborn Mets had made great strides however and were on the crest of their first world championship since 1969. But they would do it without a slumping Foster who was benched in favor of future Giants star Kevin Mitchell.

Foster hinted that the Mets demoted him because he was black. An odd statement considering Mitchell was also African-American.

Foster later clarified that he meant to say baseball preferred to promote it’s white players over blacks as role models to young fans.

But the damage was done and a personally affronted New York manager Davey Johnson arranged for the purging of Foster from the Big Apple – denying George a shot at a third World Series title.

Foster wrapped up his big league career that season – appearing in a handful of games with the White Sox.

He Never Had a (Giants) Bobblehead Day. But…

If the Giants weren’t clear in what they had in Foster when they traded him, it surely must have come sharper into focus when Foster returned to Candlestick Park with the Reds in mid-September of ‘71 for a mid-week two game set.

After back-to-back home losses to the Dodgers, the Giants’ once healthy NL West margin had dwindled to a solitary one-game lead. A year after winning the NL pennant, the Reds meanwhile had slumped in ‘71, settling into a very disappointing fifth place in the division. But Cincinnati was clearly up to playing the role of spoilers.

After taking the first game 4-2 (9/15/71), Cincinnati laid a worse beating on the Orange & Black the next day, winning 8-1 on a scorching Indian Summer afternoon.

The Reds took a slim 2-1 lead into the 8th before breaking open the contest with a five run outburst – the key strike coming on a booming, two-out Foster grand slam off Giants reliever Don McMahon.

After the game, Foster admitted he still had Orange & Black running through his veins -to a point.

“I really regretted leaving my friends and except when I’m batting I’m pulling for the Giants. I don’t want to see them blow it now,” said George after doing his best to make sure the Giants did indeed “blow it.”

The Giants would soon right the ship and clinched the West on the final day of the season with a 5-1 win at San Diego (9/30/71).

Giant Footprint

In hindsight the Giants trade of Foster was, without a doubt, a massive screw-up. But if you go back and dissect the swap from the Giants end, you can kind of see where they were coming from.

For starters, Foster was still a very raw talent when the Giants traded him. Foster had difficulty hitting the breaking pitch and struck out at a high rate (fanning in about 25 percent of his Giants at-bats).

Now, you have give the Reds credit for sticking with Foster through his painfully elongated growth period. But they could have also easily moved on from Foster at some point as well before he blossomed.

As far as the players the Giants received from Cincinnati, Geishert did not report to Triple-A Phoenix and never threw a pitch for the Giants organization, nor in the big leagues again.

But Duffy, the primary player coming back to San Francisco for Foster, was no random pick-up.

The Giants had long been enamored of the slick fielding infielder with Bay Area roots. An Oakland native, Duffy grew up in Turlock, before an impressive turn at Stanford University.

The Reds selected Duffy with their first-round draft pick of the secondary phase of the 1967 draft – apparently just as the Giants were closing in on the Pac-8 standout.

Duffy was slated to be the Reds shortstop of the future, but he was bypassed by the precocious Dave Conception, a future perennial Gold Glove Award winner and All-Star.

The Giants meanwhile we’re going with the fantastic looking rookie Speier at shortstop. Though he was knocking the cover off the ball and flashing impressive defensive skills, Speier was just 20 years old and had previously played just one season of minor league ball.

So trading for Duffy made some me sense as an insurance policy.

“After (Duffy) played at Stanford, we wanted to draft him No. 1 in 1967, but the Reds picked him off just one turn before we had our chance,” said manager Fox. “Duffy has great lateral movement which is a requisite at Candlestick on the AstroTurf. We feel he can help us at third and second base as well as shortstop.”

As it turned out, Speier never stopped playing at a high level and would be the Giants starting shortstop through the 1976 season. He returned in the late-1980s as a key utility-player.

Duffy never got much of a chance with San Francisco in ‘71, batting .179 (5-for-28) in 21 games. After the season he departed the Bay Area for Cleveland, along with Perry, in another disappointing trade for washed-up right-handed pitcher Sam McDowell.