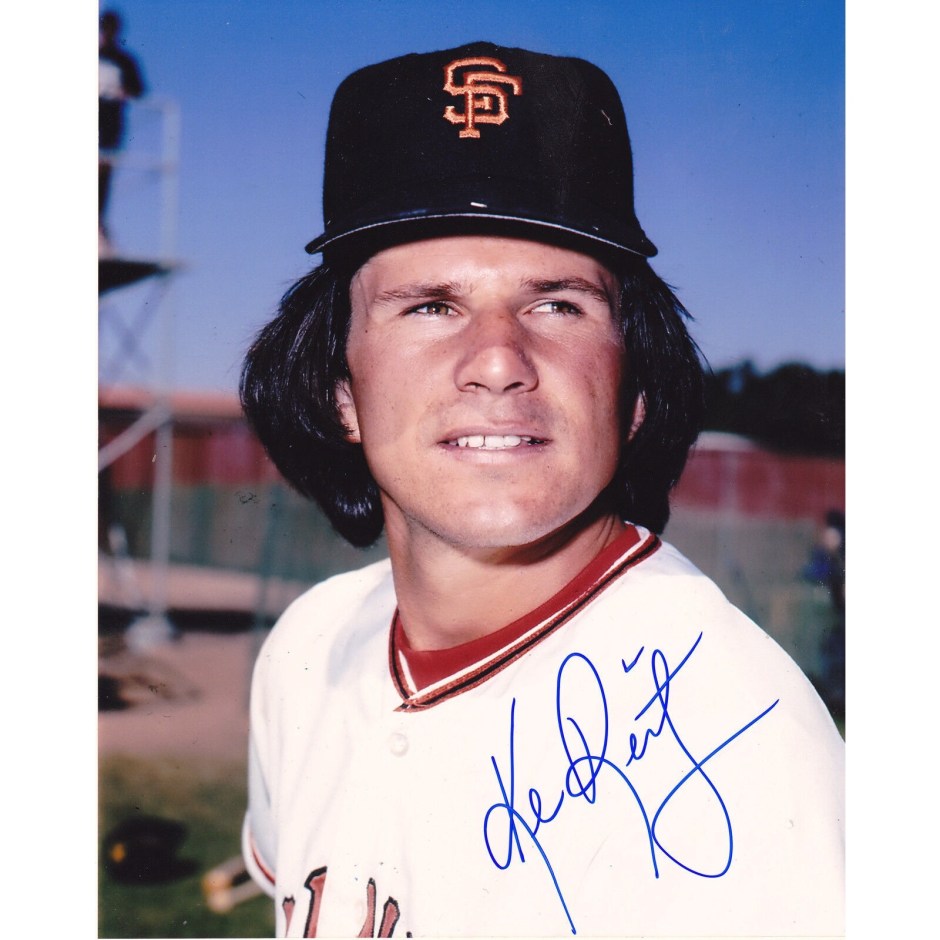

An autographed 1968 Ron Hunt picture with the San Francisco Giants (photo from ebay)

He was a Giant? Ron Hunt 1968-70 2B #33

By Tony the Tiger Hayes

Some boys shy away from playing baseball because they are afraid of getting hit with the ball. That was never the case with Ron Hunt. In 2010, Giants broadcaster Duane Kuiper memorably coined the phrase, “Torture” to characterize the numerous vexing way the team managed to win ball games in San Francisco’s first ever World Series title season.

But that wasn’t the first time the Giants or – in this case, a singular Giant – endured high levels of pain and misery while and benefiting the Orange & Black.

Forty odd years earlier, Giants infielder Ronald Kenneth Hunt took torture to a variant- more personal – level, when he became an unofficial crash test dummy for the Orange & Black.

During his three seasons with the Bay City Bashers from 1968-70, Hunt was drilled, plunked, and bonked by pitched baseballs, a staggering – pun intended – 81 times.

If given the opportunity, Hunt would typically retrieve the offending baseballs that slogged him and nonchalantly toss them back to the pitcher as if they were mere nuisances.

For seven consecutive seasons starting with his first year with San Francisco in 1968, Hunt led the bigs in getting whacked by pitchers.

He never complained.

As a Giant strictly, Hunt accumulated a combined 50 hit by pitches over 1968-69. In 1970 – his final campaign with San Francisco- Hunt set – what was then – the modern day HBP record, amassing an astounding 31 uniform tickers and flesh finders.

But Hunt was only getting the started.

In 1971 – after a trade to Montreal Expos (more on that later) – Ron took his niche skill set to a new level when he piled up a shocking 50 HBP pitches to set a non-dead ball era standard.

“He would turn his back away from the pitcher and deflect the ball with that spin move, so that he avoided those direct hits,” former Expos play-by-play man Dave Van Horne said. “To the average person, it would look like he was trying to get out of the way of the pitch, when, in fact, he just wanted to stand in there and take it.”

Overall, in his 12 big league seasons, the St. Louis native took a perpetual pummeling in the batter’s box -averaging 22 beanings per season for a whopping grand total of 243 HBP over his career.

Buoyed by his uncanny ability to get popped by pitches and a base-on-balls friendly approach to batting, the second baseman carried a lusty .368 on base percentage during his career.

Hunt is the Poster Boy for getting clobbered by pitches – and his niche baseball skill only blossomed as a Giant.

While Hunt was bonked a higher than average number of times as a member of the Mets (1963-66) and Dodgers (1967), his magnet-to-steel-like attraction to pitched baseballs really began to excel after he joined the Giants roster in 1968.

For starters, the City by the Bay’s summer-long cool climates allowed for Hunt to comfortably wiggle into an undercover hardball cushioning scuba diving suit – an accessory he occasionally employed as a New York Met – more often at frosty Candlestick Park.

But aside from feeling less agony thanks to the wet suit, you can also thank Hunt’s Giants teammates for justifying his willingness to take a batter’s box beating.

Though the scrappy Hunt had a reputation as a bit of a red ass, his Giants teammates in general didn’t have callus feelings about the apparent bullseye painted on their second basemen’s back.

But the Giants also realized Hunt’s habit for having his arms, backside and occasionally head blocking the path of fastballs was good for San Francisco’s bottom line.

While Hunt’s previous team’s lineups – especially the woeful Mets – were largely composed of journeymen and banjo hitters, his Giants bat swinging cohorts resembled a barnstorming All-Star team, with Willie Mays, Willie McCovey and Jim Ray Hart, and a phenom vintage Bobby Bonds filling out the heart of the lineup.

All Hunt had to do was get on base by any means necessary and then wait for the Giants big bats to drive him home.

Sure enough, Hunt was a top three finisher in runs scored in each of his three Giants campaigns.

Giants run totals also climbed considerably year- to- year in each his three seasons with the club.

Hunt’s single game piece de resistance came in a Giants 4-3 win over the visiting Cincinnati Reds (4/29/69) when he was walloped three times – to tie New York Giant Mel Ott’s MLB single game record – by a trio of three different pitchers: Eddie Fisher, Wayne Granger and George Culver. Hunt also collected a hit in the win.

During his stay in Fog City, Hunt had perfected his HBP skills to the point where he rarely missed any action despite the constant pitched pastings he endured.

While never admitting that he aimed to get plunked on purpose, Hunt certainly didn’t shy away from inside pitches.

“First I would blouse the uniform — this big, wool uniform, I would make sure it was nice and loose,” he once told a reporter.

“Then I’d choke way up on the bat, and stand right on top of the plate. That way, I could still reach the outside pitch. That was the Gil Hodges philosophy on hitting: The two inches on the outside corner were the pitcher’s, the rest was his. I thought, ‘If I can take away those two inches, and he’s not perfect, I can put the ball in play and get some hits. And if he comes inside, I can get on base,” Hunt concluded.

Why Was He a Giant?

While Hunt’s penchant for HBPs, was his baseball calling card, he was also part of the historic first ever trade between the San Francisco Giants and Los Angeles Dodgers.

The extremely rare player swap between the blood rivals went down a full nine calendar years after both clubs decamped New York City for California.

After spending his first four seasons of big league ball with the Mets, Hunt was traded to the Dodgers after the 1966 season. But after just one season in Southern California, Hunt was shipped to Northern California along with infielder Nate “Peewee” Oliver in exchange for the longtime Giants starting catcher Tom Haller.

A player of Hunt’s steadiness and gritty demeanor was greatly appreciated by Giants manager Herman Franks, who had grown weary of the Giants infield inconsistency in the mid-1960s.

In 1968, the reliable Hunt set the tone for his Giants tenure, appearing in 148 games (tied for tops on the club). While his .250, 2, 28 stat line was routine, Hunt boasted an excellent .371 on base percentage thanks to 25 HBP and team best 78 walks. His 79 runs trailed only Mays and McCovey on the club.

“I was taught early that there is only one way to play the game and that is to play to win,” Hunt explained. “Sliding into a base and trying to take an infielder out of the play is part of the game. I expect others to do the same.”

Hunt’s on-field production in 1969-70 campaigns were virtual redux of his Giants debut year.

In terms of regular season wins and losses, the Giants were an extremely successful outfit in Hunt’s tour with the club, going a composite 264-222, but they were not able to reach the postseason in those years.

After finishing in second place behind Atlanta in 1970, the Giants indicated they would go with a younger roster in 1971.

The 30-year-old Hunt was informed he would likely be traded or moved to a utility role.

Sure enough, the following offseason, Hunt was traded to the Montreal Expos for the obscure Dave McDonald. The young outfielder’s entire big league career had consisted of a handful of games with the Yankees the previous summer.

Despite the forewarning, Hunt was besides himself when the trade was announced. He publicly blasted former Giants managers Clyde King and Charlie Fox who replaced Franks in rapid succession after the ‘68 season.

But Hunt saved his best material for Horace Stoneham, claiming the Giants owner – a man known as a cocktail connoisseur- was quite possibly half-in-the-bag when negotiating his trade to Montreal.

“Look who they traded me for! I can’t believe that’s the best they could do,” Hunt bellowed. “Stoneham must’ve been drunk when he made the deal.”

Though he went from a club laden with star talent to a last place club, Hunt was too far along into his HBP act to play it safe, he took even more abuse in 1971 racking up 50 HBP as an Expo.

Hunt acknowledged at the time that no kid ever dreams of getting athletic notoriety for getting beaned by baseballs, but he was hardly embarrassed.

“You’ve got to be proud of getting your name in the record books – I just take things as they come,” Hunt said. “I wouldn’t change my style because if start bailing out I won’t be an effective hitter. So I might as well just stand up there and take it.”

Take it he did.

When he retired from Major League Baseball after the 1974 season, Hunt held the sport’s modern day HBP record with 243. He’s since been passed by Jason Kendall (254), Don Baylor (267) and current modern day HBP leader Craig Biggio (285). Hall of Famer Hughie Jennings – a one-time Giants manager – a dead-ball era player is the all-time official HBP leader at 287.